When Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821 CE, it was not yet a stable state.

To protect itself against Indian raids into the sparsely populated region, it sponsored immigration from the USA into Texas.

In 1836 CE that policy backfired, when the Texans revolted against the Mexican government.

In 1845 CE Texas was annexed by the USA, then led by president James Polk, who conducted an expansionist policy.

A year later war between Mexico and the USA broke out.

In the west, US forces conquered Santa Fe de Nuevo México and Alta California, while in the east, the initial fighting was inconclusive.

Despite the successes in the western theater, the war soon descended into a kind of stalemate.

Scott realized that the sparsely populated territory in the north was not vital to Mexico and conquering it would not bring the country to its knees.

So he proposed to move to Mexico City itself.

Taking the city was not the ultimate strategic objective; it was a means to bring the Mexican government to the negotiation table.

The plan was approved.

The Americans fielded an army that was initially 12,000 men strong, later reinforced.

It consisted of about 2/5 regular soldiers and 3/5 short-term volunteers.

Scott was accompanied by several officers who would later play important parts in the American civil war.

Mexico was a state, but not yet a nation; its people were divided amongst themselves and rallied no unified opposition against the American invaders.

Its army lacked training and compared to the Americans its infantry had inferior firearms.

The soldiers were not paid well and prone to desertion.

Worse, the Mexican elite had to fight not only the Americans but also internal rebellions, which were deemed the greater threat.

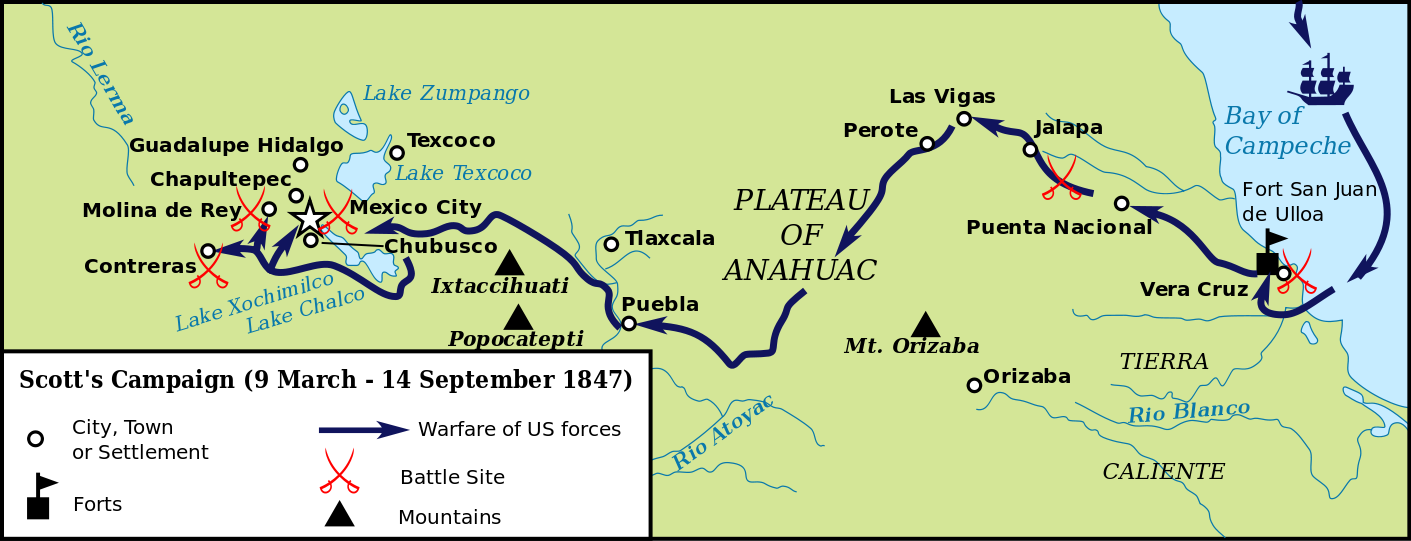

Scott did not take the straightforward overland route, but sailed across the Caribbean and landed at Veracruz.

The city was defended by 3,400 Mexicans.

Mortars and naval guns blasted a hole in the city wall and killed 400 Mexican soldiers and 400 civilians, causing the rest to surrender after 12 days.

During the siege the Americans started to suffer from yellow fever.

Scott left the sick and a garrison behind and quickly marched inland with 8,500 men, to higher and cooler places that were less prone to disease.

During the campaign he traveled over the Mexican National Highway, the only paved road,

following the same route that Hernán Cortés had taken more than three centuries earlier.

The Mexican commander, Antonio López de Santa Anna, who had been fighting in the north, quickly rushed back and blocked the Americans near Cerro Gordo.

The Mexicans had a larger army, about 12,000 strong, and a good position.

However American engineers secretly constructed a road at night and managed to get 2,600 dragoons to outflank the enemy in the north.

These same engineers would prove their value many times in the campaign, in sieges, building temporary roads and establishing supply lines.

The Mexicans fought back, but, half encircled, got the worse of the fighting and then broke and fled.

They lost 1,000 wounded and killed and 3,000 prisoners against 400 American dead or wounded.

Scott advanced to Puebla, then the 2nd largest city in Mexico, and took it without a fight.

There he paused, waiting for reinforcements, because many volunteers had served their one year term and returned home.

Scott had brought plenty of money, so the Americans could buy food from the local population

and did not have to plunder, which would have turned the whole countryside against them.

Instead looting and other crimes were repressed by strict martial law, especially on the ill-disciplined volunteers among the Americans.

Nonetheless his lines of supply and communication were increasingly harassed by guerrillas.

Scott took measures to protect them, though did not bother to become bogged down by them.

Some troops were left behind to garrison Puebla and he resumed his advanced westward.

Approaching Mexico city from the south led to battles at Contreras and Churubusco, both won by the Americans.

Then a brief armistice was concluded, but as negotiations led to nothing, Scott ended it after two weeks.

Despite a string of defeats, the Mexican army was still intact and outnumbered the Americans.

The latter won the next battle at Molino del Rey, though suffered as many casualties as the Mexicans.

Several times more costly in lives was the storming of the the Castle of Chapultepec, which was the last obstacle that barred the way to Mexico city.

After that the city gates were taken quickly.

Scott's campaign had taken half a year.

His forces were tired and battered, but morale was high.

He had carefully balanced caution with aggression, strategic objectives with tactical considerations and successfully operated deep within enemy territory.

After deliberately fighting cautiously at first, he had suffered substantial losses in the last battles, yet won each time.

After the fall of Mexico City, Santa Anna made one more attempt to cut off the American lines at Puebla, but failed.

Scott fortified his roads and cities and counterattacked the guerrillas to secure his positions.

The Mexican position was now hopeless.

They were forced to sign the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, in which they ceded Santa Fe de Nuevo México, Alta California and a large part of Texas,

in return for money to alleviate the debts of the Mexican state and the purchase of modern weapons.

War Matrix - Scott's Mexico City campaign

Geopolitical Race 1830 CE - 1880 CE, Wars and campaigns